When You Can't Write What You Do Know

"There was no way I was going to write about Charles and Emma Darwin," by RLF Fellow Emma Darwin

When you write fiction about history, as I do, you find yourself sitting on festival platforms, teaching writing courses and judging prizes for historical fiction. And at some point in the Q&A you’re sure to be asked whether there’s any truth in the old commandment to write what you know, because writers of historical fiction, by definition, don’t.

I usually point out that all fiction is made from bits and threads and scraps of real life in the real world, which we then weave and knit and stitch into new stories that never actually happened. So while the real materials of your direct experience provide, as it were, the gold standard for realness in your fiction, the true commandment for fiction writers is write what you want, and make me believe you know it.

“In fiction I feel the most intelligent, and the most free, and the most excited, when my characters are fully invented people”.

Toni Morrison

So why, when I embarked on the perfect combination of writing what I know — my (rather famous) family – and what I don’t know – a fictional story, set in the past — did my agent have to say, time and again, “Emma, I’m sorry, but it’s really not working.”

Why, in the end, did the whole thing crash and burn, and me with it?

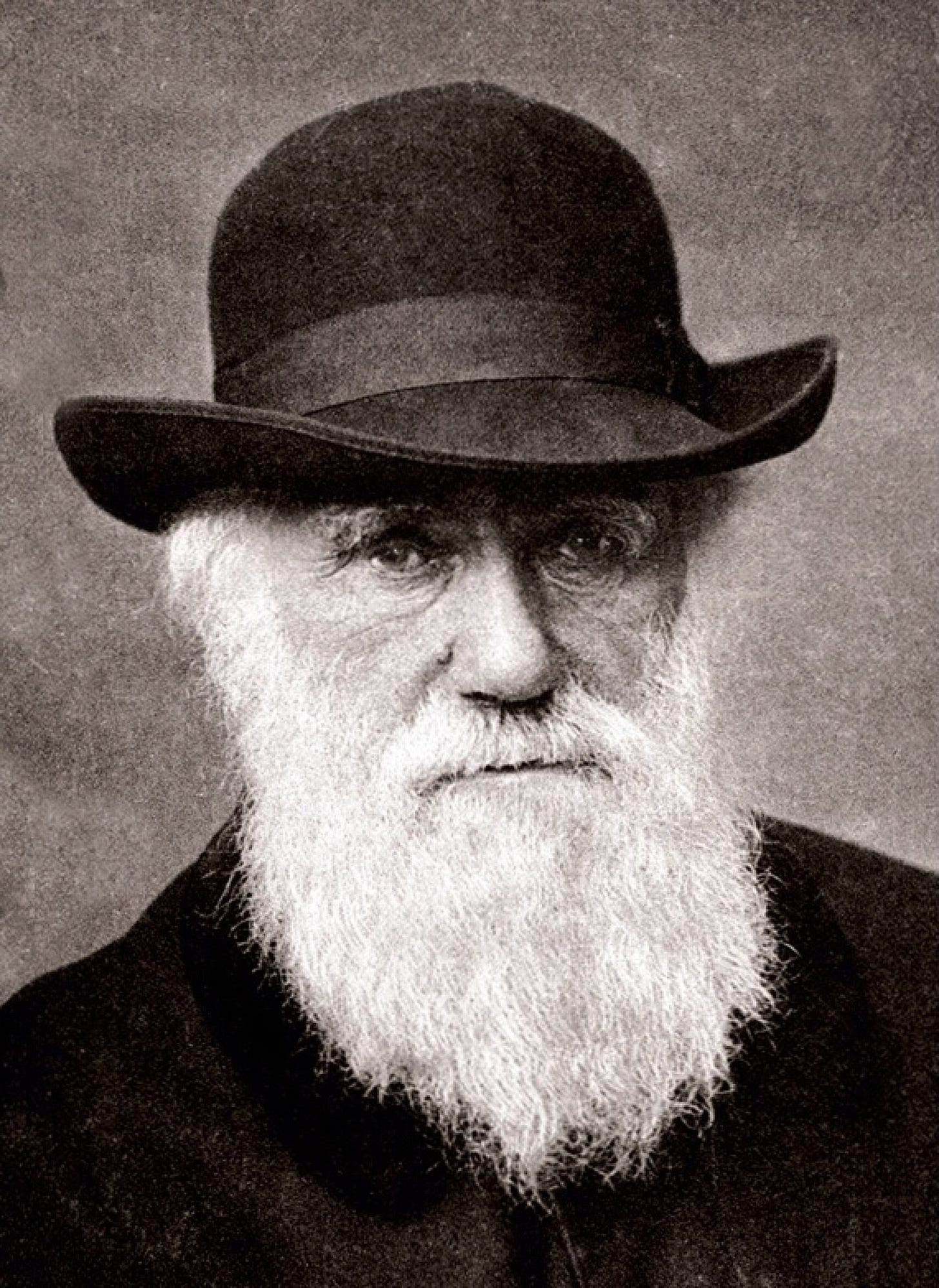

Sure, since my first novel, The Mathematics of Love, was published, I’d said to many interviewers that I couldn’t imagine writing a novel about Charles Darwin, my great-great-grandfather, and his cousin and wife Emma Wedgwood. They speak too clearly and at too much length through their own words and those of others: in the archives are hundreds and thousands of unignorable historical lines and far too little room for me to write between any of them. There are dozens of biographies, several novels, and at least one film.

My resistance has distinguished company, mind you. Of her decision to write the true story of Margaret Garner through the fictional Sethe, in Beloved, Toni Morrison said that the former “is fascinating, but, to a novelist, confining. Too little imaginative space there for my purposes.” Later, in an interview, she said, “In fiction I feel the most intelligent, and the most free, and the most excited, when my characters are fully invented people”.

No, there was no way I was to going to write about Charles and Emma Darwin.

Then the novel I was writing went irredeemably wrong, and I agreed with my agent that it would be worth investigating the wider family tree to see if somewhere in the clan there was a novel I could write — because that would be a novel that she could sell. I clambered up and began to look.

Here were Charles’s grandparents, polymath Erasmus Darwin and potter Josiah Wedgwood, and Josiah’s son Tom, often called the first photographer. Here were the scientists and engineers, of course, but also writer Julia Wedgwood, ranked by contemporaries with George Eliot; Charles’s granddaughters, geneticist Nora Barlow, poet Frances Cornford and artist Gwen Raverat; composer Ralph Vaughan Williams, and in later generations sculptor Phyllida Barlow, and poet and radical John Cornford, the first Briton to be killed on the Republican side in the Spanish Civil War. Creative thinking runs through the generations like the seams of the Staffordshire clay, which made the original Wedgwood fortune.

And here was the 1908 Cambridge University Marlowe Society production of Comus, for Milton’s bicentenary. Rupert Brooke starred, along with Frances as The Lady, and it was designed by Gwen. Onward through the First World War and the Twenties to 1931. Frances is helping surgeon and William Blake scholar Geoffrey Keynes (brother of economist J Maynard Keynes and husband of Gwen’s sister Margaret) with the book for the first full-length British ballet, Job. The music is by Ralph Vaughan Williams, the design by Gwen Raverat, Maynard’s wife, ballerina Lydia Lopokova advises, and the choreographer is Ninette de Valois.

Would this work as a novel? One thing I do know about, I reasoned, is creative process and how art gets made: I am a writer, and both my first degree (Drama and Theatre Arts) and my doctorate (Creative Writing) are in practice-led disciplines. Surely here was real-life stuff, stuff that I knew, which I could take and make my own?

I elbowed some space between the lines by imagining a fictional Imogen — a lonely only child who Gwen and Frances befriend, whose fiancé, another Erasmus Darwin, is killed at Ypres, and whose great comfort is her godson, baby Rupert John Cornford – and got cracking.

“Emma, I’m sorry, but it’s really not working,” said my agent, yet again.

Other novelists work brilliantly with such close-up, biographical material – Jill Dawson, for example – but my original reluctance was proving well-founded. Every time my creative imagination began to run, my Inner Historian yanked on the leash, crying, ‘But could it have happened like that? What if it didn’t?’ And ‘Of course it matters!’

It’s fiction, I argue on other writers’ behalf in class and on platforms. If readers want history, they should buy a history book. But this book would be billed as about the Darwin family. The further I strayed from the record of these lives, the more I changed, imagined or invented, the more I realised we’d be touting a book which was nothing like the “truth”, whilst simultaneously, and — most shamefully of all — selling it using my famous surname.

I sought help from writer friends, I cried on shoulders, I tried again and again. And then, partly from the pressure of trying to write a novel while earning a living, I became, temporarily, very ill.

As I convalesced, I slowly realised it wasn’t that I was stupid, or had got it wrong, or wasn’t trying hard enough at this project. The thing is, when you grow up in a family like mine (and my mother’s family are just the same), you soon learn that in talking about anything, points should be properly made, supported with accurate facts, and connected up into a logically provable argument. Anything you put forward may be tested and questioned, and whoever has the best facts, the best argument, or has earned the right to authority in the topic, must be acknowledged as being the winner — even if it’s not you.

Only fiction is entirely mine: sovereign territory where my authority doesn’t have to be earned, where my imagination can run, intelligent, free and excited, as I build my world and embody my ideas in whatever plot and characters I decide work best. In fiction I can speak my creative truth. Yet in trying to write a novel about my family, whenever I tried to speak and the historical record said No, I was silenced. No, I couldn’t build my world, write my story, say what I wanted to say, because someone else had greater authority.

Three centuries of the family habits of thought had bred these fascinating people – and bred, above all, Charles Darwin, who was why any of this was happening and why I could hope people would buy this novel – but it had also bred me. The reason I was writing this novel was the reason I would never be able to write it.

Only when I’d given up completely on the idea of writing about the family as fiction did it occur to me that there might be another way. Creative non-fiction — life writing, memoir — is a form which is developing fast and fascinatingly; it’s one vast liminal area, with gloriously fuzzy boundaries. In the field of creative non-fiction, a book about creative thinking in my family, as seen through the lens of my creative failure to write a novel about them, made perfect sense.

And so, at the busiest time of my teaching year, the first draft of This is Not a Book About Charles Darwin: a writer’s journey through my family fell out of my pen and onto the page in about six weeks. Finally, I was writing what I knew.

Emma Darwin’s debut The Mathematics of Love is probably unique in being simultaneously nominated for the Commonwealth Writers Best First Book and RNA Novel of the Year awards; her second novel, A Secret Alchemy, was a Sunday Times besteller. She is also the author of Get Started in Writing Historical Fiction, and her latest book is the memoir This is Not a Book About Charles Darwin. She teaches creative writing at Oxford University and Goldsmiths, University of London, and has given workshops from Auckland to Zurich. She holds a PhD in Creative Writing, and her blog

is linked to by writing courses around the world.

I realise reading this I actually HAVE written novels around some of the characters and events she describes here - Lydia Lopokova and Maynard Keynes in the 1920s. But I'm certain I couldn't have done it if they'd been "family" or perhaps even if they'd had direct descendants. There's a need to be able to make a subject your own, when you start imagining it into fiction, and a legacy, even if on the face of it a positive one, can be a real burden.

Please tell Emma Darwin I absolutely agree with her article. I wrote Snow Widows using creative nonfiction techniques- the Times called it ‘masterly’ but only the experts believed it was non fiction. So this time around with Behind Everest (as Kate Nicholson) I have taken the ‘polar’ opposite approach. I did that creative fiction course at Kellogg! I would really enjoy a chat with Emma about ‘truth’ and truth. So fascinating…