Ukraine’s writers at war, and the life and death of Victoria Amelina

RLF Fellow Julian Evans on fragmented storytelling, writing about war, and the work of Victoria Amelina and many other Ukrainian writers

Two years ago today, Ukrainian writer Victoria Amelina was injured during a Russian attack on Kramatorsk and died of her injuries a few days later. This week her unfinished book Looking at Women, Looking at War won the Orwell Prize for Political Writing.

In this piece, RLF Fellow Julian Evans – author of Undefeatable: Odesa in Love and War – explores how Ukrainian writers like Amelina and others living through war write about their reality.

At the beginning of the Noughties, when frankly this century looked more promising than today, I spent two years travelling across Europe with a digital recorder and a microphone. My job was to talk to novelists, 156 in total, including four Nobel Prize laureates, for a BBC radio series about the rise of the modern novel. In complete truth, I can say that these two years of talk – where did the novel come from? What was it for? Where was it going? – were among the most interesting of my life. But only one of the conversations has stayed with me, to the letter.

How do you make words express the completely new situation of war?

The Polish writer Tadeusz Konwicki (1926–2015) and I were sitting in his modest apartment in central Warsaw. We were discussing something I had been aware of for some time, but been unable to find an explanation for: namely, the difference between the generally linear storytelling of British fiction and the tendency of novels in mainland Europe to tell more disrupted, fragmented stories.

Konwicki had an answer to the question, from a Pole’s point of view. In World War Two, as a member of the underground resistance after his country was occupied by Nazi Germany and the Soviet Union, he had experienced years of ground war and fighting against violent occupation.

“My generation,” he said, “was the generation of people who, time and again, had to face the possibility of their lives being threatened, when you see your whole life in a split second. The traditional narrative structure couldn’t express the psychological insight of the situations we found ourselves in.”

The words of this charming, softly spoken Polish novelist stayed with me. For a decade, I found them a shrewd literary observation. In the next decade, I started to feel them as a statement of much more direct relevance. In the 1990s, I had fallen in love and got married in the Black Sea city of Odesa, and I have been visiting (and writing about) Ukraine for more than 25 years. In 2015, after Vladimir Putin first invaded the east of the country and stole Crimea, I travelled to the front line near Donetsk and Mariupol because I simply didn’t believe the Western reporting I was hearing. It had no understanding of Ukraine’s history, or its sovereignty; in their place, Western media were all too ready to soak up and re-broadcast Russia’s propaganda and disinformation.

Fast forward seven years, and when Russia launched its all-out aggression in 2022, I went back to live in Odesa again. I wanted to see if I could do anything to help, and to share what life was like in the blacked-out city under attack. I also felt too safe in England. Ultimately, the feeling you’re not where you belong, it bugs you.

“The traditional narrative structure couldn’t express the psychological insight of the situations we found ourselves in.”

Tadeusz Konwicki (1926–2015)

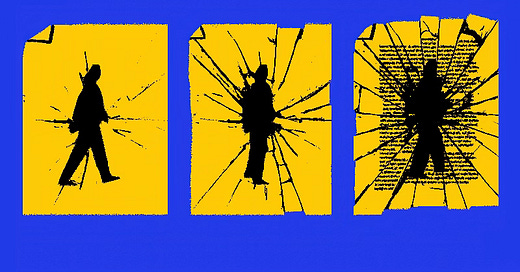

When, a few months afterwards, I started to write a story of the city and my involvement with it, I faced a similar task to my friend Konwicki’s. How do you make words express the completely new situation of war? My first attempts were a failure: you cannot make sense of war by pretending that it has sense, or is logical. I tried again. One day, I started to weave two stories together. One was about the past’s peace, the other was about the war’s events; I chopped in episodes, physical sensations; I described how in war people make normality go on, then things change in a split second. And because I’m not Ukrainian, I also started looking at the lives of Ukrainian writers under conditions of war. Things started to fit together.

In its barbaric, greedy attempt to swallow Ukraine, Russia has blown up far more than cities and villages. It has exploded millions of Ukrainians’ personal stories, along with their stories of what and where they belong to. Writers and artists find themselves in the forefront of this chaos. Looking for ways to process these physical, emotional and psychic shocks, they find themselves at the same time especially hated and in the firing line of the occupiers, standing for a love of truth and a Ukrainian culture that Russia claims does not exist.

This, Russia’s Big Lie that Russia and Ukraine are ‘one people — a single whole’, is not in any way new. Ukrainian writers have fought Russia’s attempts to suppress their culture for hundreds of years. Taras Shevchenko, Ukraine’s national poet, was exiled for over ten years in the late 1840s and 1850s and forbidden to write. The Ukrainian language went underground after being banned in 1863. In the USSR in the 1930s, Stalin imprisoned and murdered hundreds of Ukrainian-language modernist poets, writers and artists who had flourished in the lenient 1920s — Ukraine’s ‘Executed Renaissance’. In 1985, almost the last political prisoner to die before the Soviet Union crumbled was the marvellous Ukrainian poet Vasyl Stus, who foreshadows Ukraine’s latest resistance against Russia in his lines ‘The shards of our pain / keep calling us to battle.’

You cannot make sense of war by pretending that it has sense, or is logical.

Which brings us to today. In which, given Russia’s gluttonous appetite for violent imperialism, history is repeating itself. In increasing numbers since 24 February 2022, Ukrainian writers and artists have been killed in the defence of their country and language. Writers like the poets Maksym Kryvtsov, killed in action in January 2024, and Myroslav Herasymovych, killed last November. Other writers have been singled out by the occupying forces: Volodymyr Vakulenko, a children’s author, was taken by Russian paramilitaries in spring 2022 and his body later found in a mass grave with clear signs of torture. Many more, like the writer Stanislav Aseyev, have been detained and tortured over years and managed to survive. But not, most recently and horrifyingly, the 27-year-old journalist Viktoriia Roshchyna, whose body was returned from the occupied territories this February with numerous signs of systematic torture and, in a not so subtle ‘message’, with her brain, eyes and larynx missing. Do not look at Russia’s actions. Do not think about them. Do not talk about them, the body wrapped in white plastic says.

Such acts by Russian forces are not isolated. It was reported in Ukraine on 23 February 2022, the day before the all-out invasion, that Russia had ordered 45,000 body bags. They could not have been for Russian casualties: the Russian army was meant to take Kyiv within days, with casualty figures in the low hundreds. The body bags were meant for Ukrainians. Russian forces in the occupied territories came with lists of names of community members who were to be treated in different ways — murdered, tortured, recruited, kidnapped, and so on. What is most shocking about the cruelty on the Russian side is that it was, and is, so organised and prepared.

How are we to respond to such enormity? The Ukrainian writer Victoria Amelina, in her impassioned and tragically unfinished new book Looking at Women Looking at War, believed that documenting the aggressor’s crimes was essential.

Amelina was a talented novelist and children’s writer from Lviv who, when Russia’s all-out aggression began, began training and working as a war crimes researcher, interviewing survivors and witnesses, travelling the length and breadth of Ukraine under Russian bombardment to collect evidence.

Her book is profoundly moving for many reasons. One is that her ambition went further than writing a war diary, into embracing her encounters with women who, like her, have felt impelled to resist. To Oleksandra Matviichuk, the lawyer and 2022 Nobel Peace Prize winner, she wrote that “despite all our efforts, we still might lose. If we lose, I want to at least tell the story of our pursuit of justice.”

The other reason is that her unfinished text, some of it only interview notes and first drafts, is, with its painful inconclusion, a potent reminder that war not only shatters linear stories but also destroys those writing them. It was on the evening of 27 June 2023 that Amelina was talking to some Colombian journalists at a pizzeria in the frontline town of Kramatorsk. She was about to leave Ukraine to take up a writing residency in Paris and be reunited with her husband and son, but had accompanied the journalists to Kramatorsk to help provide context and background. As they were talking, a Russian Iskander missile targeted the pizzeria. The Colombians were not seriously hurt, but Amelina suffered severe head injuries and died five days later. She was 37.

Mindful of her book’s urgency in bearing witness, Amelina wrote it in English. She was right. It’s clear that Europe still has difficulty identifying its fate with Ukraine’s. A book such as hers provides proof that the actions of Ukraine’s tormentor are not one-off, randomly violent, opportunistically murderous. It underlines that a form of genocide has been, and is, going on in Ukraine, most forcefully in the occupied territories. This is genocide in the strict sense of signifying a deliberate assault on the culture, language and values of a group of people “with the aim of annihilating the groups themselves”, in the words of Raphael Lemkin, the Polish lawyer who coined the term in 1944.

Victoria Amelina’s unfinished text, some of it only interview notes and first drafts, is, with its painful inconclusion, a potent reminder that war not only shatters linear stories but also destroys those writing them.

Writers may not bear arms or wear military uniform, although many in Ukraine do, and writing cannot protect anyone physically or bring them back to life. But in a war whose aim is forced assimilation and the erasure of truth, identity and culture, as writers stand for the pursuit of justice and set out from the beginning to make words mean something again, they are, in Ukraine, on a deadly frontline of their own. It is also ours, both as writers, and Europeans.

Julian Evans is a biographer and travel writer. He is the author of Undefeatable: Odesa in Love and War (Scotland Street Press, 2024).