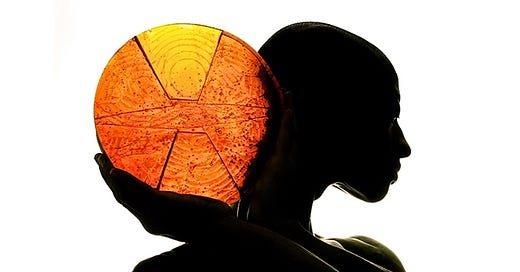

No Facts, Only Versions: Thoughts on Memoir

Plus WritersMosaic celebrates their third anniversary and launches a new imprint with The Jhalak Foundation and The Bookseller

WritersMosaic is three years old! A division of the Royal Literary Fund, WritersMosaic is an online magazine and developmental resource focused on UK writers of the global majority. The platform showcases writer profiles through authored talks, creative exchanges and interviews. Recently WritersMosaic featured writers and musicians celebrating the centenary of James Baldwin (1924-87).

To be a black person in America, James Baldwin once said, was to be “in a state of rage almost all of the time.”

Coinciding with the anniversary, WritersMosaic and The Jhalak Foundation launch the first issue of The Review, a biannual insert into The Bookseller. The Review will be produced by and feature writers of the global majority, both in and outside the UK and will be “first and foremost a space for complex and comprehensive literary discussions, and debate that addresses the imperial gaze and moves beyond its reach” according to The Review team.

In this month’s WritersMosaic, their guest edition focuses on memoir. No facts, only versions is edited and curated by WritersMosaic director, Colin Grant.

“Memoirs are as much about what is excluded as what is included,” writes Colin. No facts, only versions features writers Hannah Lowe, Clementine Burnley, Nick Rankin, Sanjida O’Connell and Phil Okwedy.

It sets out to explore the art of memoir writing, and asks how to “evoke the truth in writing memoirs whilst drawing on memories that are sometimes fallible or contested.”

Colin Grant, whose memoirs are Bageye At The Wheel and I’m Black So You Don’t Have To Be, writes that:

“Jamaicans will tell you that when it comes to the truth, there are no facts, only versions…However, I dispute the first part of this Jamaican assertion. There are verifiable facts but in recounting them in writing, memoirs give us versions of those facts. Memoirists’ accounts are not acts of bad faith; more often than not, writers trade the attempt to capture empirical truth for a quest for emotional truth.”

The stories I’ve told have sometimes been contested by family members. I’ve always answered relatives who complain that I have got things wrong with a simple retort: ‘This is my version. If you don’t like it, you’re free to write your own.’ Colin Grant

Hannah Lowe in Searching for Nelsa Lowe describes looking for her Aunt Nelsa, one of her father’s half-Afro half-Chinese sisters:

“A photograph, a brief mention in a newspaper, a death certificate, a man who knew my aunt in passing fifty years ago. How to reconstruct her life, with so little to go on?

And whose story is it to tell?”

Hannah Lowe

Nicholas Rankin writes about the anxiety of autobiography. In Trapped in History: Kenya, Mau Mau and Me, Nicholas brings himself fully into the story for the first time in any of his books, but then struggles with telling his family’s story, and writing about himself as a child as well as about the oppression of black Kenyans from the perspective of a white man.

“Trapped in History is about not being free in beautiful Kenya. Yes, a sunny garden crowned our 22 acres, but we lived in a bungalow with barred windows, an iron gate in the corridor and a siren on the roof. My parents carried a gun. We were in plenty, but amid poverty.”

Nicholas Rankin

Clementine E Burnley’s preface to The Stranger’s Quarters talks about living in a small town, Limbé (previously known as Victoria), in Cameroon.

“Being a Victorian involved speaking a certain kind of Patwa, well-thumbed English books, hand-embroidered white doilies, beige antimacassars, macrame plant pot holders, black polyester waist-slips, organza-trimmed hats, Silver Cross prams, Girl Guide uniforms, Raleigh bicycles, washing machines, wood-burning stoves, and Morris Minors. Each of those objects had a story. Everything came from ‘England’.”

Clementine Burnley

Sanjida O’Connell shares the first chapter in her memoir, Wilderness: In Search of Belonging, about growing up a dual heritage child in rural Britain, the search for her origins, and seeking solace in rewilding a small fragment of Somerset.

“One of my favourite photos is of me in Nigeria aged two with two men. The man who is holding me is dark-skinned, with a large nose and kind eyes. He’s wearing a white, sleeveless shirt. His hair is cut short to his scalp, but you can still see the Afro kink.

The other man, solid, white, beaming, his hair as black as boot polish, is in a cassock with a collar.

A Catholic priest and a Muslim mathematician.

My two fathers.”

Sanjida O’Connell

Sanjida is serialising her nature memoir on Substack.

Sanjida O’Connell in conversation with Phil Okwedy. Phil is an oral storyteller. The Gods Are All Here is his one-man show about growing up dual heritage (Welsh and Nigerian) in Wales, his search to discover who his mother and father really were, after discovering a cache of letters his father had written to his mother, interwoven with stories inspired by West African folk tales.

“Storytelling is cinema for the mind but unlike a film the story is only really present, only really alive, when there is a teller to tell an audience and imagine it.

Having been born not quite Welsh, definitely not Igbo cause I didn’t grow up there, I lacked a myth. So I started creating my own.”

Phil Okwedy