Living by her pen: how the forgotten Gothic writer Regina Maria Roche's legacy lives on

For Women's History Month, Samiha Begum shares her story of discovering RLF beneficiary, Regina Maria Roche, as part of her PhD on Gothic female writers

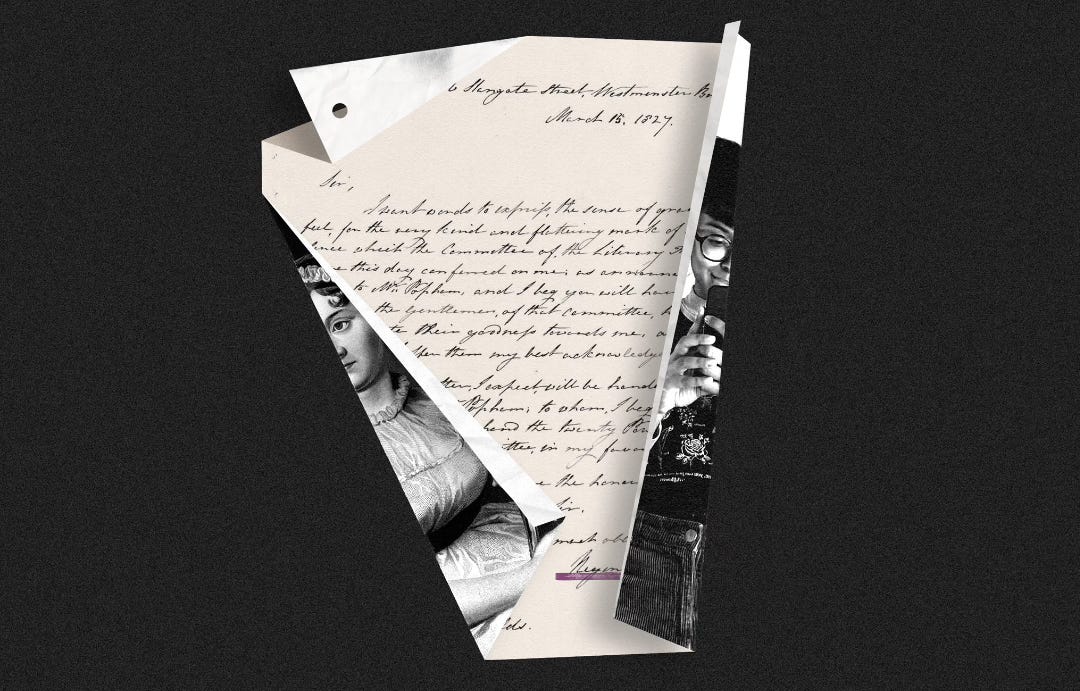

Earlier this year, University of Sheffield PhD student Samiha Begum’s thesis exploring the Gothic sublime in the works of four female writers – Ann Radcliffe, Eleanor Sleath, Charlotte Smith and RLF beneficiary Regina Maria Roche – brought her to the British Library, where she spent time exploring letters Roche wrote to the Royal Literary Fund in 1827.

Like many eighteenth- and nineteenth-century female writers, Regina Maria Roche struggled to make a living during her lifetime. This is even though she wrote prolifically, and was one of several writers whose gothic fiction novels helped define the genre. If you have ever read Jane Austen’s Northanger Abbey or Emma you might recognise the titles of two of her books – Clermont and The Children of the Abbey.

Samiha, whose research interests centre around theories of the sublime, landscapes, and feminist ecological criticisms, explains:

“I was originally drawn to my research topic as there really isn’t enough research on Gothic women writers in the late eighteenth and early nineteenth century – recently there’s been more about Radcliffe, but there’s still barely anything on Sleath and Roche.”

This is where Roche’s letters to the RLF come in – they help to provide some context about her life and work during a period of time that was essential to the development of the gothic novel.

So with all that in mind, here is Samiha to give us some more background about this forgotten gothic fiction writer, as we celebrate Women’s History Month and International Women’s Day:

“The person, be it gentleman or lady, who has not pleasure in a good novel, must be intolerably stupid.”

Northanger Abbey by Jane Austen

This quote from Northanger Abbey (1817) is one of the top results in Goodreads’ book quotes section. It’s a pretty great quote, but I believe the passage after is the most significant.

It continues, “‘I have read all Mrs. Radcliffe’s works, and most of them with great pleasure. The Mysteries of Udolpho, when I had once begun it, I could not lay down again; - I remember finishing it in two days - my hair standing on end the whole time.’”

You may have heard of Ann Radcliffe (and if you haven’t, here is a good place to start) as Radcliffe served as inspiration for other notable authors during the eighteenth and nineteenth centuries, including Austen herself. However, there is another author mentioned in Northanger Abbey who you may not know, and that is Regina Maria Roche. Roche was influenced by Radcliffe and had her own commercial success at the time of her writing. Importantly, she was also a Royal Literary Fund (RLF) grant applicant, which allowed her to continue writing in an unsteady and expensive part of her life.

Roche was born in Waterford, Ireland in 1764 (the exact date is unknown), and published sixteen novels in her lifetime. Her first two novels were published under her maiden name, Dalton, and she moved to London after marrying Ambrose Roche. It was the success of her third novel in 1796, The Children of the Abbey, that brought Roche into the spotlight with her writing. Her fourth novel, Clermont, was published soon after in 1798, and was similarly popular and is the novel featured in Northanger Abbey along with the other six so-called “horrid novels” that Isabella Thorpe recommends to her friend and Northanger Abbey’s protagonist, Catherine Morland:

“I will read you their names directly; here they are, in my pocketbook. Castle of Wolfenbach, Clermont, Mysterious Warnings, Necromancer of the Black Forest, Midnight Bell, Orphan of the Rhine, and Horrid Mysteries. Those will last us some time.”

Interestingly, it was assumed for many years that Austen had invented all the novels and authors on this “horrid” list of gothic novels. Only in the 1920s did scholars Michael Sadleir and Montague Summers discover the novels Austen had listed were all real. The authors on this list also include Eliza Parsons – another RLF beneficiary, who wrote The Castle of Wolfenbach (1793) – and Eleanor Sleath, who wrote The Orphan of the Rhine (1798).

Roche reached out to the Royal Literary Fund for monetary support around 1826, when she was faced with legal issues to do with her husband’s estates and a dishonest solicitor.

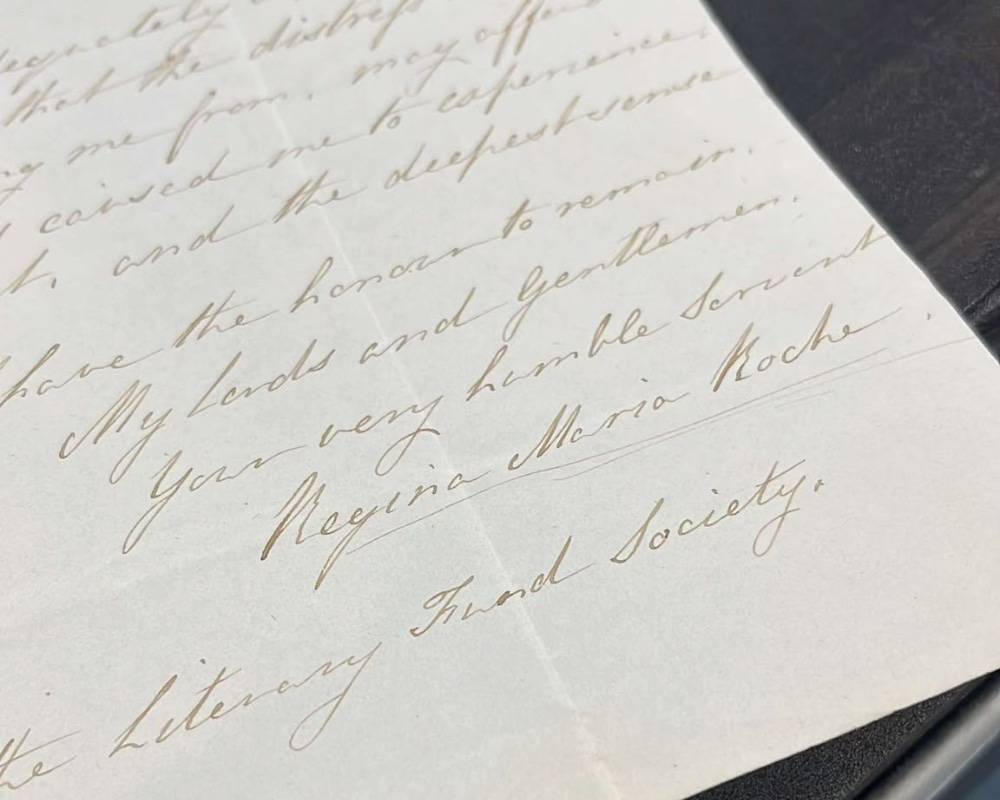

She had many friends advocating for her writing and was supplied with a grant from the RLF. In a letter dated 15 March, 1827, Roche wrote to the Royal Literary Fund (then known as the Literary Fund Society) thanking them for their “kind and benevolence” actions as instigated by Edward Popham, a close friend. Popham had written to the RLF advocating for Roche, and it was with this help that Roche was awarded £20 (this would equate to just shy of £1,800 today).

Correspondence between Roche, the RLF and her other sponsors is currently housed in the British Library. I had the wonderful pleasure of viewing some of these letters in person, and it was such a fantastic opportunity to see Roche’s handwriting, her signature, and her words at a time when she was genuinely struggling and trying to live by her pen. It was clear that Roche loved to write and lived to write, and after her monetary setbacks were resolved, she continued to do so until her last published work in 1834. The letters in the RLF’s collection are a valuable and important resource, not just for academics like myself but for anyone interested in literature, women’s writing, or the RLF.

It is difficult not to draw parallels between Roche and myself, as we have had quite similar experiences. Fortunately, I have never had to deal with a shady solicitor, nor have I published sixteen novels (one can dream, though). Still, I do understand the struggles of being a writer worrying about money. It’s a hard truth to ignore when you are a working class woman of colour writing in a world tailored towards middle class white men. However, organisations such as the Royal Literary Fund are a shining beacon for writers, as they provide support, financial aid, and guidance to writers, all the way from Roche’s time of need in 1827 to this very moment.

We asked Samiha to tell us more about her thesis, and what drew her to the work of female gothic fiction writers like Regina Maria Roche. You can also visit the Digitising Women Writers project for more information, including a full Regina Maria Roche reading list.

Tell us how you began your academic career

Samiha Begum: I grew up in London and completed my BA in English at Queen Mary, University of London. It wasn’t until the third year of my undergraduate degree that I really thought about further studies. Pursuing an MA seemed like the right approach, even though it was the height of the pandemic and I had no real idea what to do after finishing university. All I knew was that I loved research and literature – maybe it was naïve of me to go into further studies with just these two things but it seemed to have worked out pretty well so far!

What initially drew you towards studying writers of gothic fiction?

SB: I started my MA in English at the University of Sheffield in October 2020, and it was during one of my modules that I discovered Ann Radcliffe for the first time. From that moment on, I knew I would love to continue researching her (and the other wonderful women writers I’m currently writing on). I discovered Eleanor Sleath and Regina Maria Roche while reading more of Radcliffe’s work on my own time. Charlotte Smith is a new addition to my thesis, but I am drawn to her just as much.

Can you explain a bit about the process of writing a PhD?

SB: I guess every PhD is different and everyone has their own way of researching! My process definitely isn’t linear, nor is it actually productive, but it works for me. I usually end up taking a loose thread of an idea and then pulling on it obsessively. Usually it means I’m (re)reading my primary source text a bunch of times and annotating it until my brain melts, then I move onto finding secondary sources through databases/journals/anthologies/libraries. Basically, when something hurts my brain too much, I move onto another part of research and then I keep going with that pattern. None of it is linear, like I said – I chose to start writing my third chapter first as it was one of the loose threads I came across. I think the next thing I write will either be the fourth or the first chapter – I’m not sure yet! I also have to plan my working hours around my part-time jobs as I’m unfunded. It all sounds messy but works for me, and I think that’s all that matters!

Featured British Library Archive images © All rights and credit go to the owner. No copyright infringement intended.

Interested in applying for a grant?

If you are a professional writer like Roche and unable to write due to a change in circumstances, you can find out more about our Grants programme on our website.